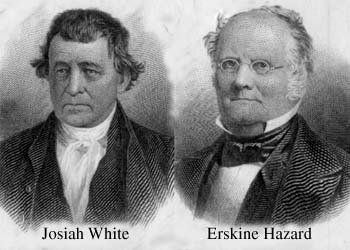

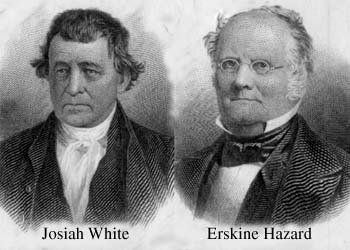

The first few decades following the American Revolution was a volatile, but exciting era -- an era filled with potential. Josiah White, a young Philadelphia Quaker who would come of age on March 4, 1802, would taste the excitement and potential and leave his mark on the Pennsylvania valley known as the Lehigh. Others would participate as well. Ebenezer Hazard, the nation's first postmaster, would found, for example, the Insurance Company of North America. Coincidentally, his son, Erskine Hazard, would become Josiah White's friend and partner. German immigrant, George Frederick August Hauto, joined the team as well. The Industrial Revolution stood poised to spread through these new United States of America, and many recognized the great potential that lay in the unexploited states west of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. President Jefferson recognized the potential and sponsored the development of a superhighway to the West -- the Lancaster turnpike. Transportation was key because, without development, moving goods to market cost more than the goods themselves. Farmers in the West, for example, distilled grain alcohol to convert corn into a more economical form for transport to market. Besides, it was undoubtedly more in demand in that form anyway!

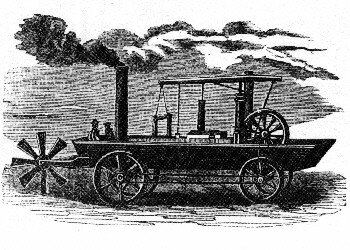

Experimenters like Oliver Evans of Philadelphia foresee the important role that transportation would play in moving products between the West and the eastern harbor cities. Believing that amphibious transportation might be important, he builds the "Orector Amphibolos," which foretells the bold innovations that were to come. Josiah White has a burning in his belly. Filled with an urge to innovate, which he would later demonstrate again and again, he becomes an ironmonger -- a dealer in hardware -- on his twenty-first bithday, and he resolves to make himself independent by the age of 30 so he can follow his innovative desires. At about this time, a boatman by the name of Turnbull delivers 200 bushels of "stone coal" to Philadelphia. The coal was picked from the ground at a site about ten miles from the Moravian mission of Gnaddenhutten on the Lehigh River. Potentially competitive with costly British coal, there were two problems -- it was difficult to burn and the primitive transportation was too unreliable and costly.

Experimenters like Oliver Evans of Philadelphia foresee the important role that transportation would play in moving products between the West and the eastern harbor cities. Believing that amphibious transportation might be important, he builds the "Orector Amphibolos," which foretells the bold innovations that were to come. Josiah White has a burning in his belly. Filled with an urge to innovate, which he would later demonstrate again and again, he becomes an ironmonger -- a dealer in hardware -- on his twenty-first bithday, and he resolves to make himself independent by the age of 30 so he can follow his innovative desires. At about this time, a boatman by the name of Turnbull delivers 200 bushels of "stone coal" to Philadelphia. The coal was picked from the ground at a site about ten miles from the Moravian mission of Gnaddenhutten on the Lehigh River. Potentially competitive with costly British coal, there were two problems -- it was difficult to burn and the primitive transportation was too unreliable and costly.

President Jefferson declares an embargo on foreign goods and that motivates the development of American alternatives to British iron goods. In response, White turns to manufacturing wire and nails and, in 1810, patents a machine for "rolling and moulding" iron. Now teamed with Hazard, White experiments successfully with dams and locks on the Schuylkill River.

Another delivery of stone coal -- this time nine wagonloads -- arrives in Philadelphia, and White and Hazard try some at a price of $40 per ton. Of this, $28 is the cost of transportation alone. Understanding the significance of a local source of fuel, White and Hazard think they can tame the Schuylkill River and open sources of fuel in that river's valley. Petitioning the state legislature for a charter to improve navigation on the Schuylkill, they are denied -- with the reminder, "It don't burn!"

In 1814, two scows full of coal survive a trip on the Lehigh River. Five started the trip at Lausanne near Mauch Chunk. The scows relied on freshets, strong local surges of water, to overcome the shallows and rapids on the river -- except for the three that didn't make it. White and Hazard buy both boatloads. And, accidentally, they discover how to burn it. The cost was higher than British or Virginia coal. But with improved transportation, it promises to be competitive and perhaps even superior! They negotiate a deal with Jacob Weiss to open and exploit these coal lands of the Lehigh Valley. The success of the deal depends on a three-part plan --

They reconnoiter the Lehigh Valley at Christmas 1817. The two partners are joined by Hauto, who (in German) convinces the legislature to support their plan. It approves the plan with, "Gentlemen, you have our permission -- to ruin yourselves." The team of three leaves for the Lehigh Valley in 1818, and work starts in Spring at the planned loading place on the river, Mauch Chunk. By the end of the year, they employ 500 workers at 75 cents a day.

On Mauch Chunk creek, which feeds the Lehigh, they develop a unique "bear trap lock," which is patented in 1819. "Immense stones were dragged from the mountains for lock-walls. A trough was constructed on the riverbed. The walls were completed, the trough done. Water was let in from a reservoir under a construction which seemed like overlapping cellar doors. A pool gathered. The lock-tender opened a sluice beneath a gabled platform -- and water pressure in the pool, against the dam created by the gable, pushed the platform flat. The downcoming boat could swoop forward on a long wooden chute thus made. On the high breast of water, the craft floated safely and smoothly over the rapids."

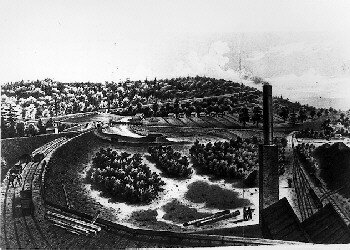

Initially, the navigation achieved on the river is descending only, since, as yet, there is no practical way of returning the boats up river. Hence, the arks are broken up in Philadelphia, where the wood is sold as lumber, and the metal fittings are returned by horse and mule to Mauch Chunk for reuse. Hauto describes the new town of Mauch Chunk "with forty buildings now, gristmill, etc. ... ," and the road between the mine and the loading dock: "The road is on ground between M. Chunk and our principal mine, ground that can hardly be compared to any other more unfavorable, for production of a good road. But, we have constructed a good road in three months. And most of it in winter. On it, a horse can draw four tons with ease. And on this road we have sufficient number of teams to haul several thousands of bushels dailey."

The reason so little power is needed to draw a four-ton load of coal is because the road was "the first road in the United States, laid out with instruments, scientifically, on the principle of never rising." It is downhill, all the way! With descending river navigation achieved and with a good road from Summit Hill to the Lehigh at Mauch Chunk, the first fleet of arks with 365 tons of coal makes it to Philadelphia in June 1820, four years ahead of plan. The Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, as the White, Hazard, and Hauto endeavor is now called, has the right product at the right cost at the right time. Demand almost immediately outstrips supply.

The reason so little power is needed to draw a four-ton load of coal is because the road was "the first road in the United States, laid out with instruments, scientifically, on the principle of never rising." It is downhill, all the way! With descending river navigation achieved and with a good road from Summit Hill to the Lehigh at Mauch Chunk, the first fleet of arks with 365 tons of coal makes it to Philadelphia in June 1820, four years ahead of plan. The Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, as the White, Hazard, and Hauto endeavor is now called, has the right product at the right cost at the right time. Demand almost immediately outstrips supply.

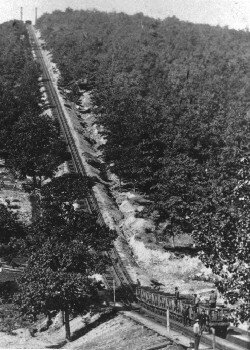

The road from Summit Hill to Mauch Chunk, which can be unreliable in bad weather, proves to be a bottleneck to increasing supply. Considering the third leg of their plan now justified, they start to convert the road to a railed road in January 1827, and they complete the work of installing iron strapped wooden rail in May. This nine-mile Down Track moves coal-laden cars downhill powered solely by gravity. Like the trip on the river, gravity provides descending navigation on the Down Track. The railroad was called the "Summit Hill-Mauch Chunk Railroad." Unlike the river navigation, the coal cars are not broken up once they are unloaded onto the river arks. Rather, they are returned uphill on the Down Track by mules.

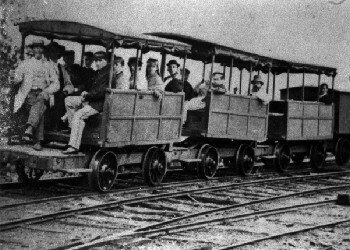

Although the make up of both downbound and upbound trains varied, one documented make-up is logistically complex, but effective. A train bound for Mauch Chunk on the Down Track consists of seven cars, each laden with as much as four tons of coal. Two such trains comprise a section. For every three sections (six trains with a total of 42 coal wagons), a separate train is sent down with seven mule wagons, each laden with four feeding mules. Now, upon arrival and unloading at Mauch Chunk, teams of eight mules are attached to trains, each of 14 now empty coal wagons. (Using 24 mules in total to return the 42 empty coal wagons.) That leaves a team of four mules to return the seven empty mule wagons.

Although the make up of both downbound and upbound trains varied, one documented make-up is logistically complex, but effective. A train bound for Mauch Chunk on the Down Track consists of seven cars, each laden with as much as four tons of coal. Two such trains comprise a section. For every three sections (six trains with a total of 42 coal wagons), a separate train is sent down with seven mule wagons, each laden with four feeding mules. Now, upon arrival and unloading at Mauch Chunk, teams of eight mules are attached to trains, each of 14 now empty coal wagons. (Using 24 mules in total to return the 42 empty coal wagons.) That leaves a team of four mules to return the seven empty mule wagons.

In 1845, the White and Hazard team builds engine houses with stationary steam engines atop the peaks of Mt. Pisgah and Mt. Jefferson, and inclined planes are graded up the eastern slopes. Now, trains of empty wagons can be staged for return at the foot of Mt. Pisgah and drawn to the peak by the stationary steam power. Then, from the peak, they return westward by gravity to the foot of Mt. Jefferson. Again, the cars are drawn to that peak again by stationary steam power. From that summit, they coast to loading points near Summit Hill. Now, the return bottleneck is gone. Traffic flows in a continuous loop like the train around a Christmas tree -- loaded cars running down the original Down Track and empty "lights" returning on the new track that would come to be called the Back Track.

The mules, rendered obsolete by technological innovation, no longer constitute a production bottleneck and are put out to pasture -- or to work in the mines.

At about this time, new mining operations are opened in the Panther Valley, which lies on the northern side of Sharp Ridge, on whose southern side runs the Summit Hill-Mauch Chunk Railroad. Since it seems logical to gain access to the gravity railroad from that site, two additional planes are developed to haul loaded coal wagons from the valley floor to Summit Hill, where trains can use the Down Track to get coal to the river. The return of empties from the top of the Mt. Jefferson plane to the valley floor is made by gravity. Too steep for a straight schuss down the mountainside, a series of "switchbacks" are laid down the side of the ridge to allow a series of back and forth maneuvers to take cars down the mountainside. Somewhere between 1845 and 1870, the railroad becomes known as the "Mauch Chunk, Summit Hill and Switchback Railroad."

At about this time, new mining operations are opened in the Panther Valley, which lies on the northern side of Sharp Ridge, on whose southern side runs the Summit Hill-Mauch Chunk Railroad. Since it seems logical to gain access to the gravity railroad from that site, two additional planes are developed to haul loaded coal wagons from the valley floor to Summit Hill, where trains can use the Down Track to get coal to the river. The return of empties from the top of the Mt. Jefferson plane to the valley floor is made by gravity. Too steep for a straight schuss down the mountainside, a series of "switchbacks" are laid down the side of the ridge to allow a series of back and forth maneuvers to take cars down the mountainside. Somewhere between 1845 and 1870, the railroad becomes known as the "Mauch Chunk, Summit Hill and Switchback Railroad."

Although passengers were occasionally carried on the railroad as early as 1829, it is largely a coal road -- the first in the country. But, by 1872, the steam locomotive has become practical, and the Nesquehoning Valley Railroad opens the Panther Valley coal mines. As a result, the Switchback's coal-hauling operations decline, but the railroad adapts and evolves to a purely tourist operation. Borrowing the catchy part of its most recent name, it becomes known as "The Switchback." By 1898, the tourist road is acquired by the Central Railroad of New Jersey*.

Although passengers were occasionally carried on the railroad as early as 1829, it is largely a coal road -- the first in the country. But, by 1872, the steam locomotive has become practical, and the Nesquehoning Valley Railroad opens the Panther Valley coal mines. As a result, the Switchback's coal-hauling operations decline, but the railroad adapts and evolves to a purely tourist operation. Borrowing the catchy part of its most recent name, it becomes known as "The Switchback." By 1898, the tourist road is acquired by the Central Railroad of New Jersey*.

Josiah White and his partner Erskine Hazard are now long gone, but we continue to learn more of their fundamental impact on early American transportation and on the early coal-mining and iron industries in Eastern Pennsylvania.

Their gravity railroad is gone too, but its marks and its memories remain -- at Mt. Pisgah, at Five Mile Tree, at Mt. Jefferson and its crossing, on the Home Stretch, ..., and in the souvenirs that remain from the collections of those who were fortunate enough to ride the Switchback. It will not be forgotten.

* - The web site housing the Jersey Central information also includes the Lehigh and Susquehanna and information on trains in general.